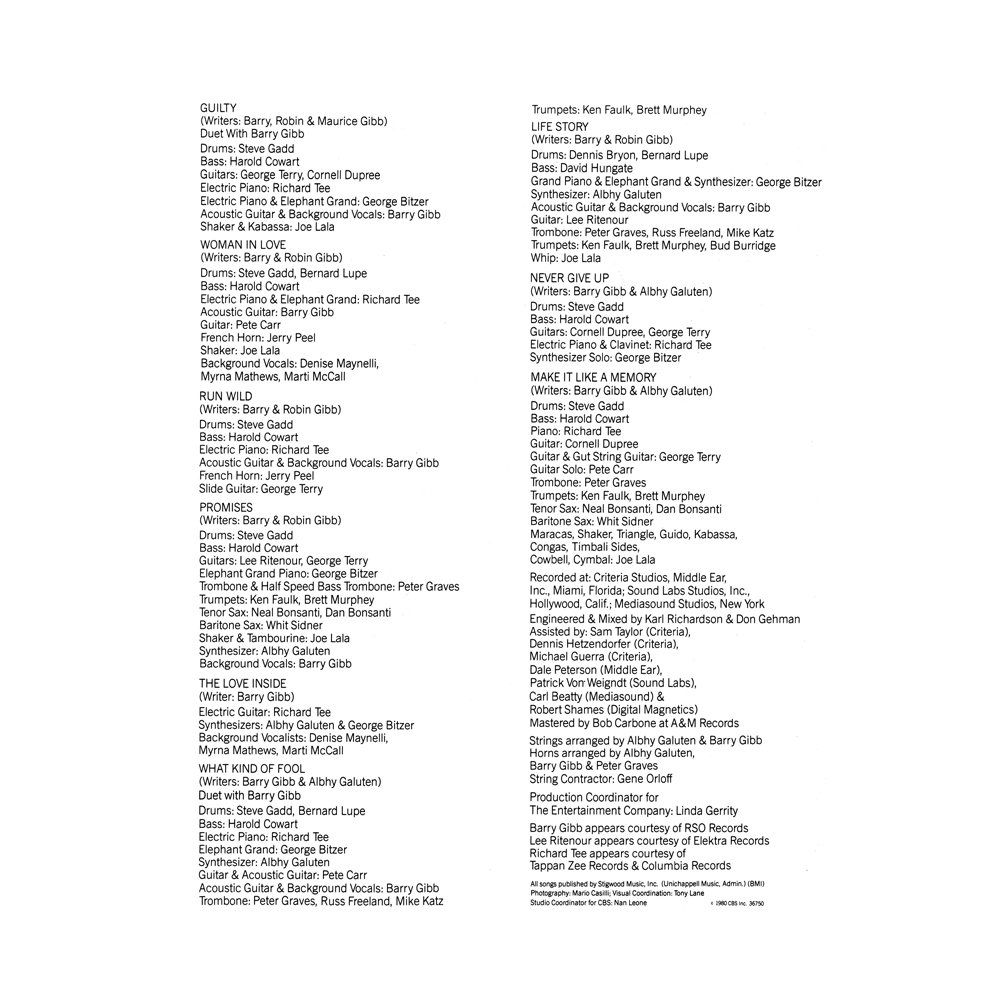

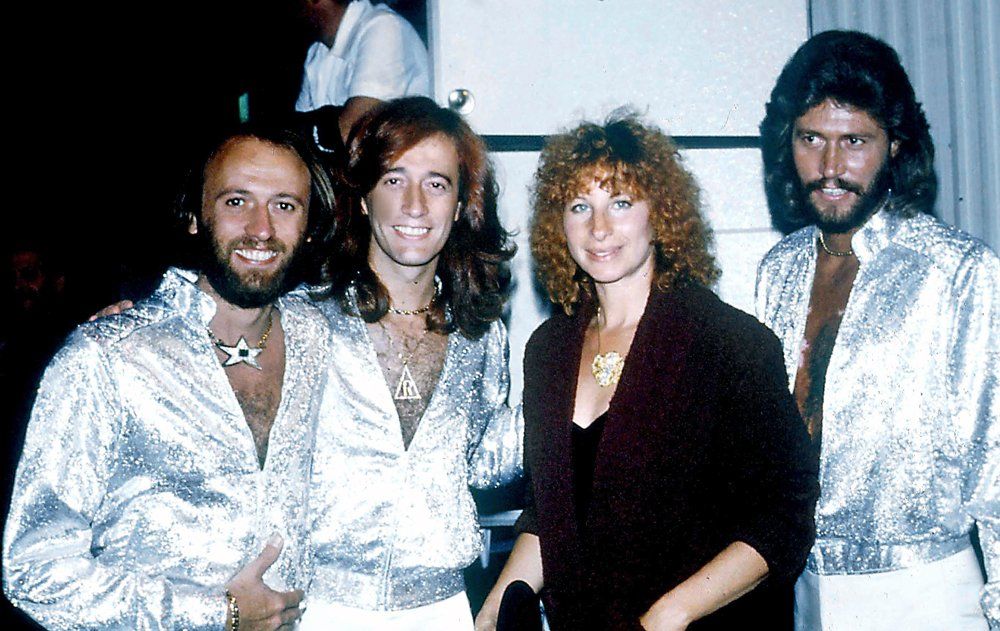

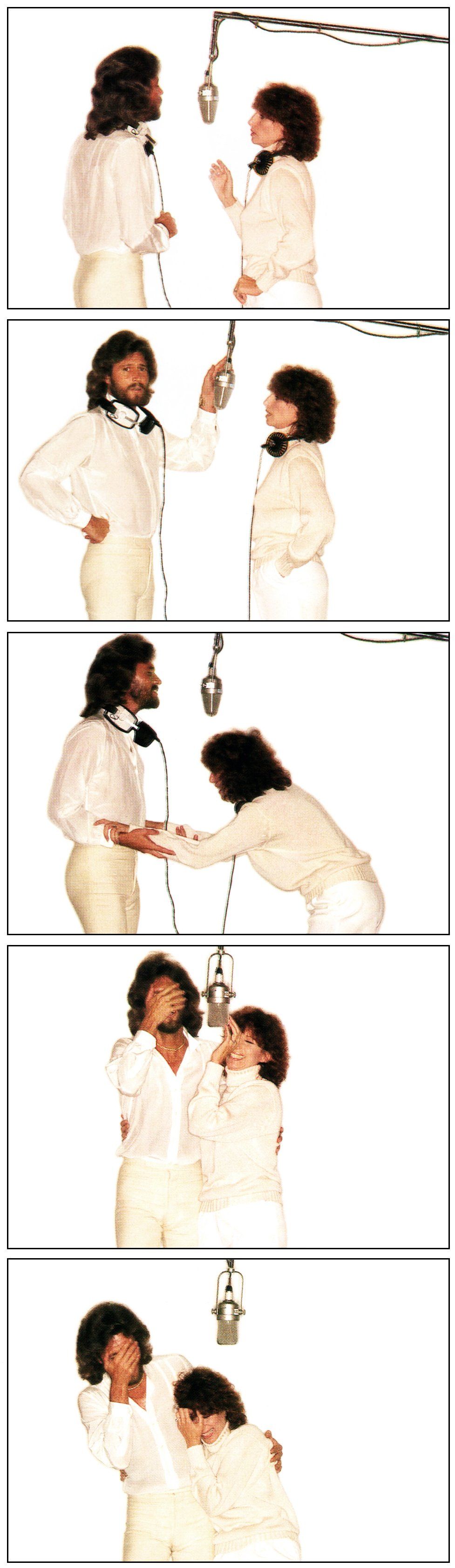

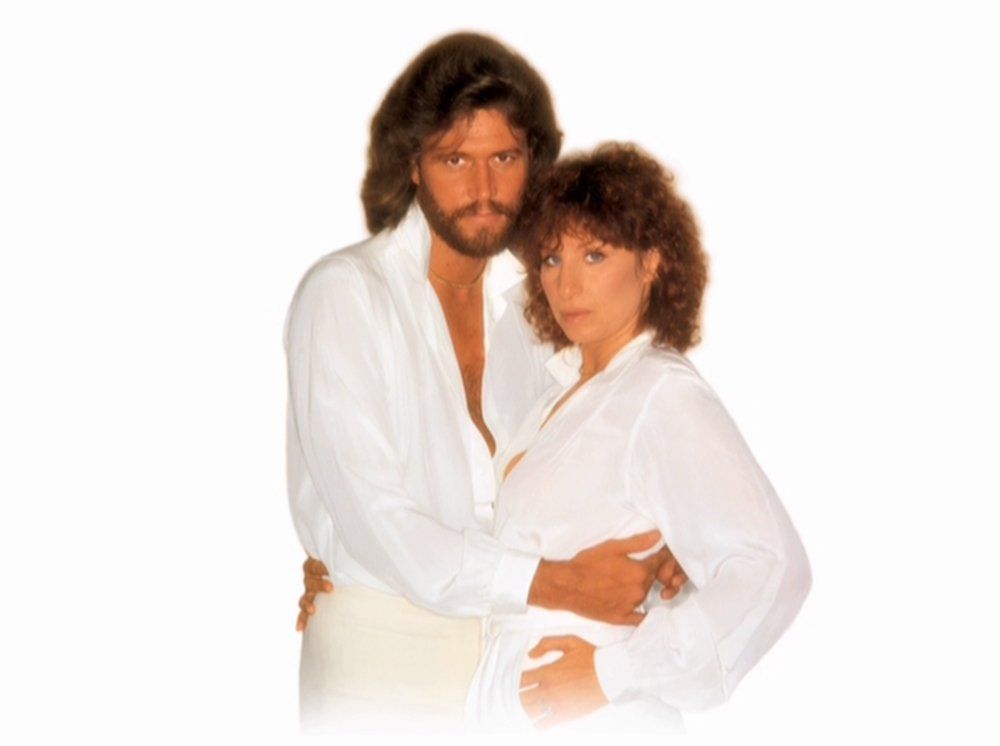

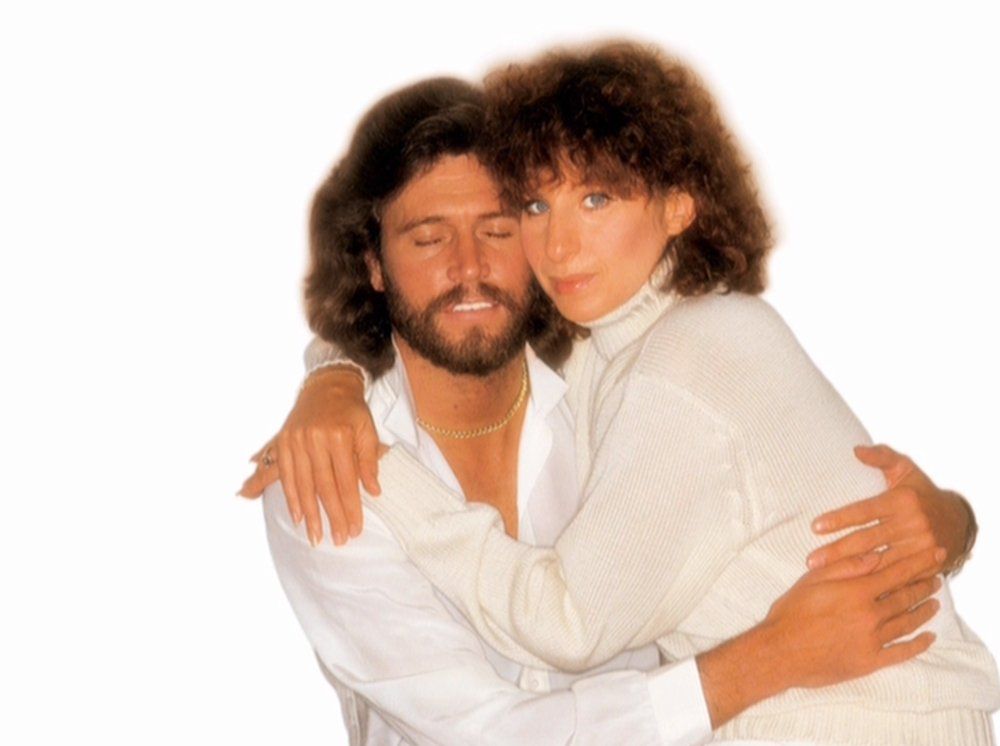

For the duet, “Guilty,” the production team had to adjust Barry Gibb's vocal. “When we recorded ‘Guilty,’ we’d already cut the track,” Galuten said. “Originally, Barry was not going to do any duets. They talked him into it. So, for his verses, we had to change the key and had worked out modulations to go from one key to another, from verse to chorus, and then overdub the instruments, fit them in, and fly that stuff around to literally create the verses for Barry that were in another key. Wherever Barry sang verses, those were never recorded in that key—they were originally recorded in different keys in different parts with everything but the drums.”

“It took us two weeks to combine the vocal,” Richardson explained. “I spent days in the studio with an oscilloscope and looking at her and the rhythm of the song and moving things in milliseconds because, again, these are rhythmic songs, [sings, emphasizing the beats] ‘and we got nothing to be guil-ty of…’ and all that stuff. You’ve got to have that nailed. She wasn’t exactly there all the time.”

Galuten added: “Barry’s feeling and his vision is that meter is pretty much on time. There’s a beat and it goes right there. And the same thing with the pitch—you don’t really scoop into pitches, you just…you’re supposed to hit the pitch and nail it. So, in order to adjust Barbra’s vocal so that it met with Barry’s sensibility, we were moving the time—and this was before the days of sampling and being able to move vocals around—with these little tiny offsets and fractions and punch-ins and delays. And doing the same thing with harmonizers to do three or four passes at the beginning of a vocal word so it would hit it right on and not slide up the way Barbra liked to do.”

“I had two machines locking up, and punching a cross-fading machine into the recording machine was a several week process to do that for the entire album,” Richardson recalled. “I had a book of lyric sheets…I think I used a loose-leaf binder that was about six inches thick by the time we got done with the album with all my notes. Every little nuance with ad libs or breaths, because you have to cross them before breaths, and things like that. From a technological perspective, when you listen to Guilty you don’t realize that behind the scenes, a lot of editing was going on.”

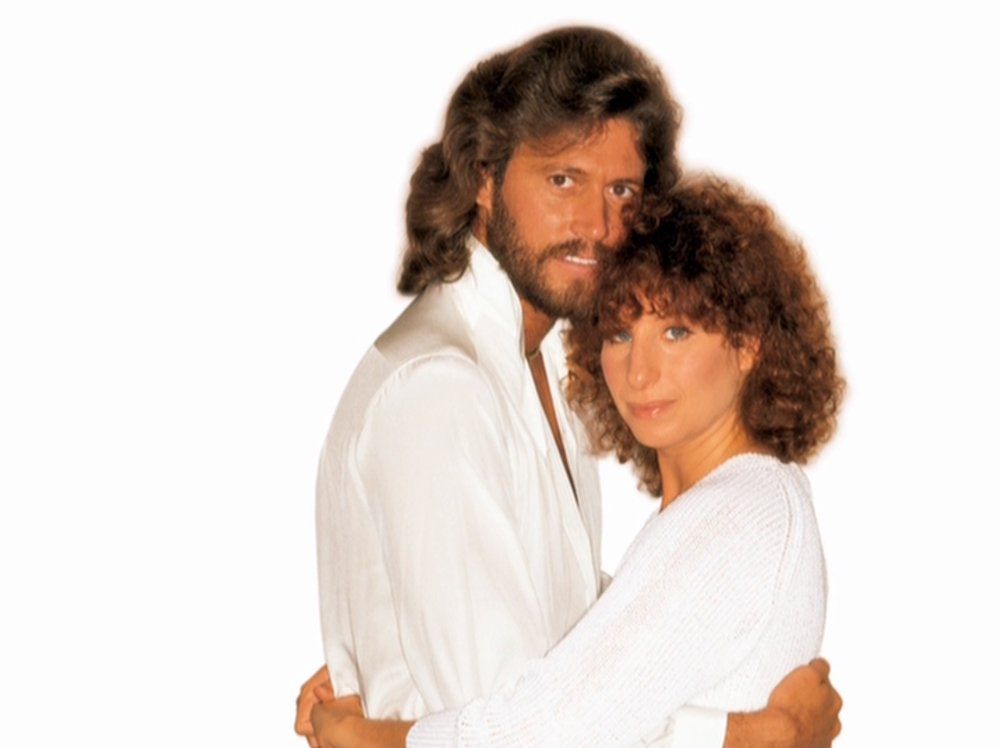

The producers took extra care on the song “What Kind of Fool.”

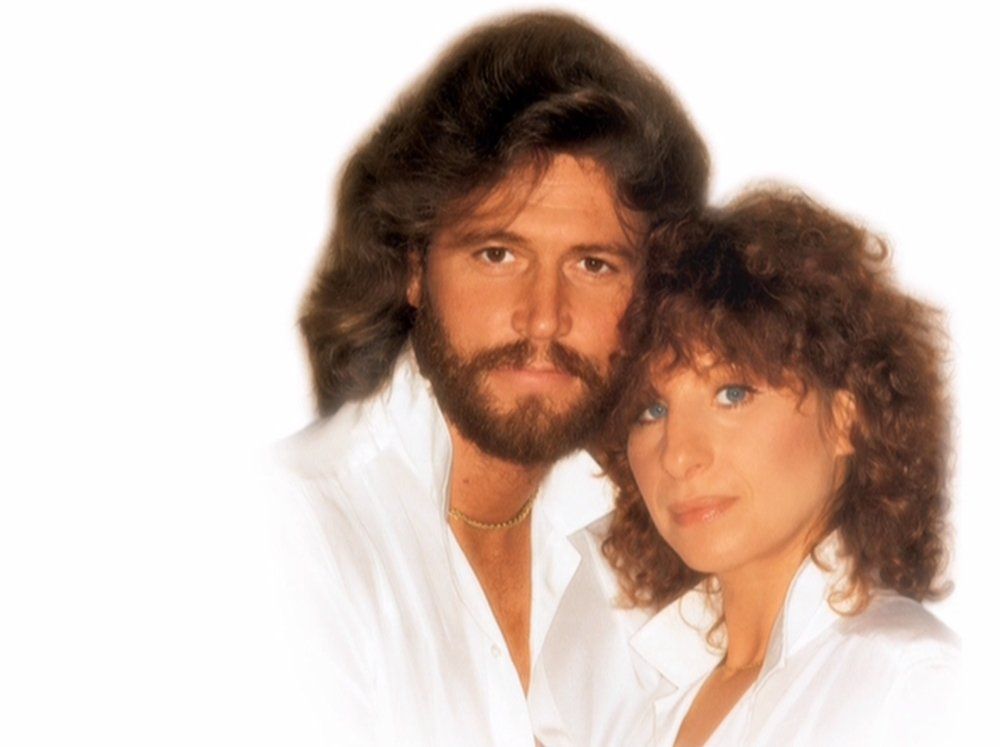

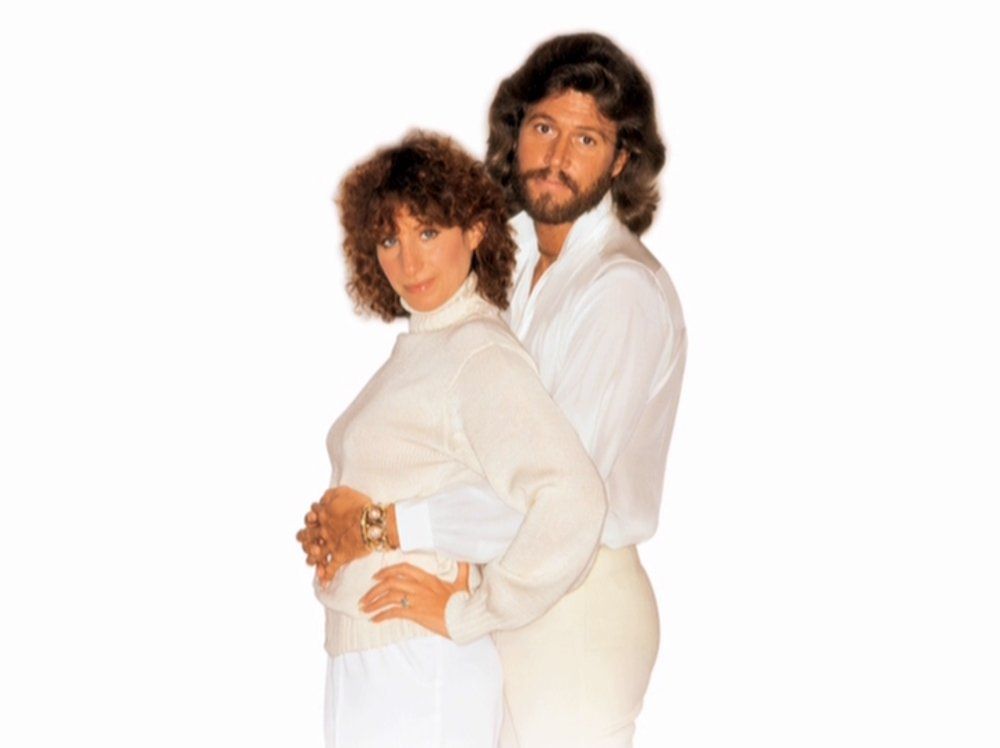

Not originally intended as a duet, they spent months exploring the right balance of Streisand's and Gibb's voices and which lines they would sing.

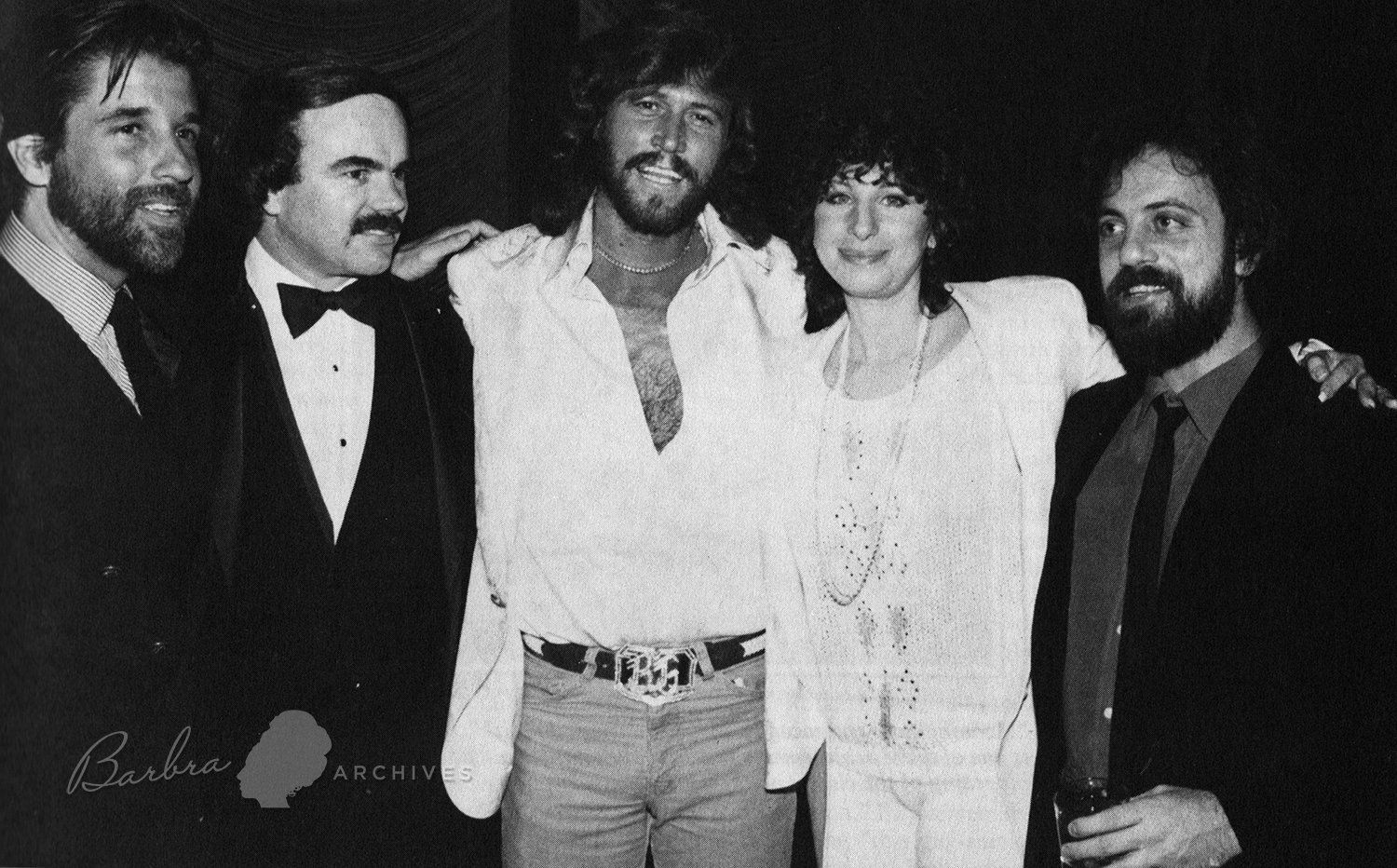

Albhy Galuten recalled that “the duets were done after the fact. This record was put together by Charlie Koppelman … It was Barry’s idea to do the record, but it was Charlie’s idea that they should do some duets. Charlie’s probably all along thinking, ‘Barry’s a hot property, we should do some duets, it’ll make the record sell.’ Well, we converted the songs to duets after Barbra was gone. She had already come and sung.”

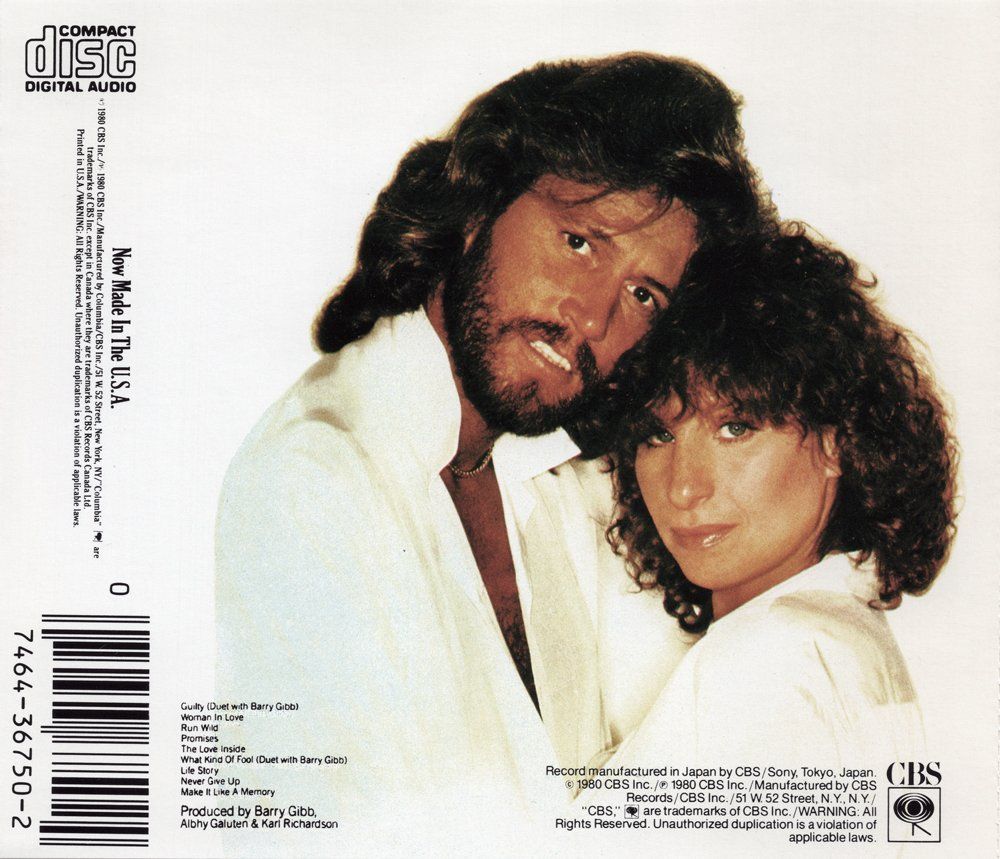

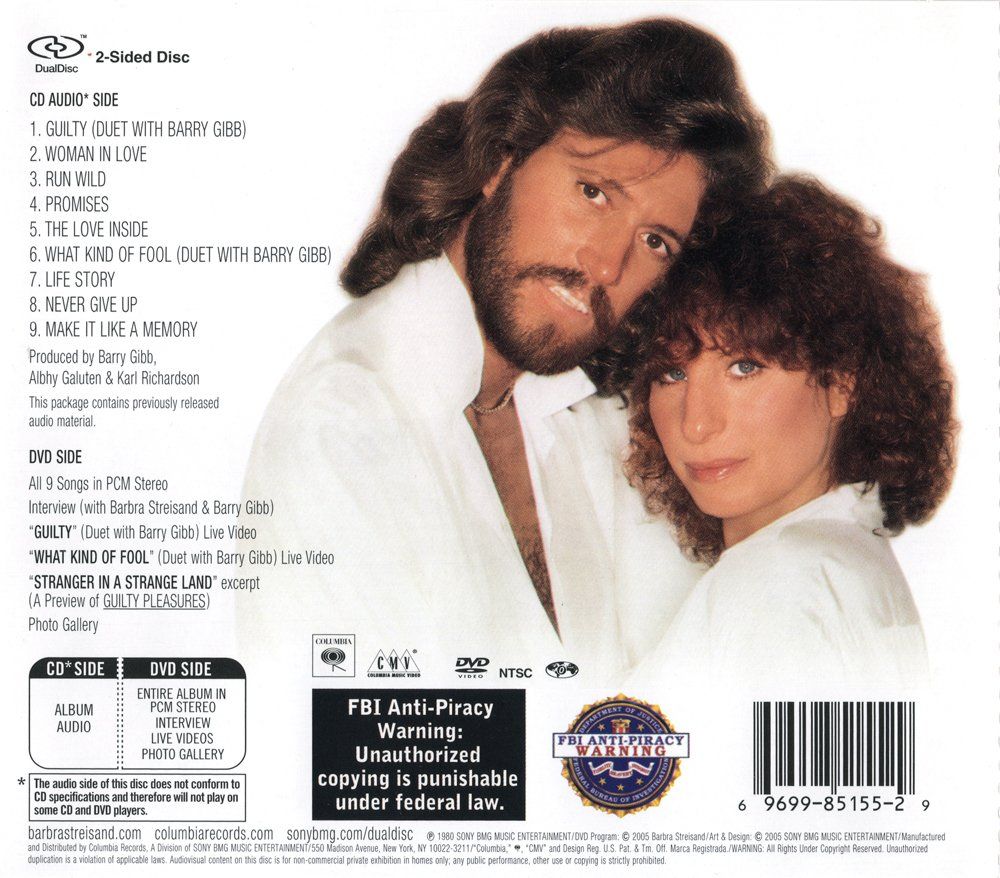

The drummer “Bernard Lupe” is credited on “Woman in Love,” “What Kind of Fool,” and “Life Story.” Lupe is not a real person – in the days before digital editing and sampling, engineer Albhy Galuten invented a “tape loop” which was lifted from two bars of the song “Night Fever.” Because their drummer’s father died in the middle of a recording session and they were unable to replace him, the tape loop of his rhythmic drumming was necessary to complete the song. Galuten reused the loop on the Guilty

album’s tracks.

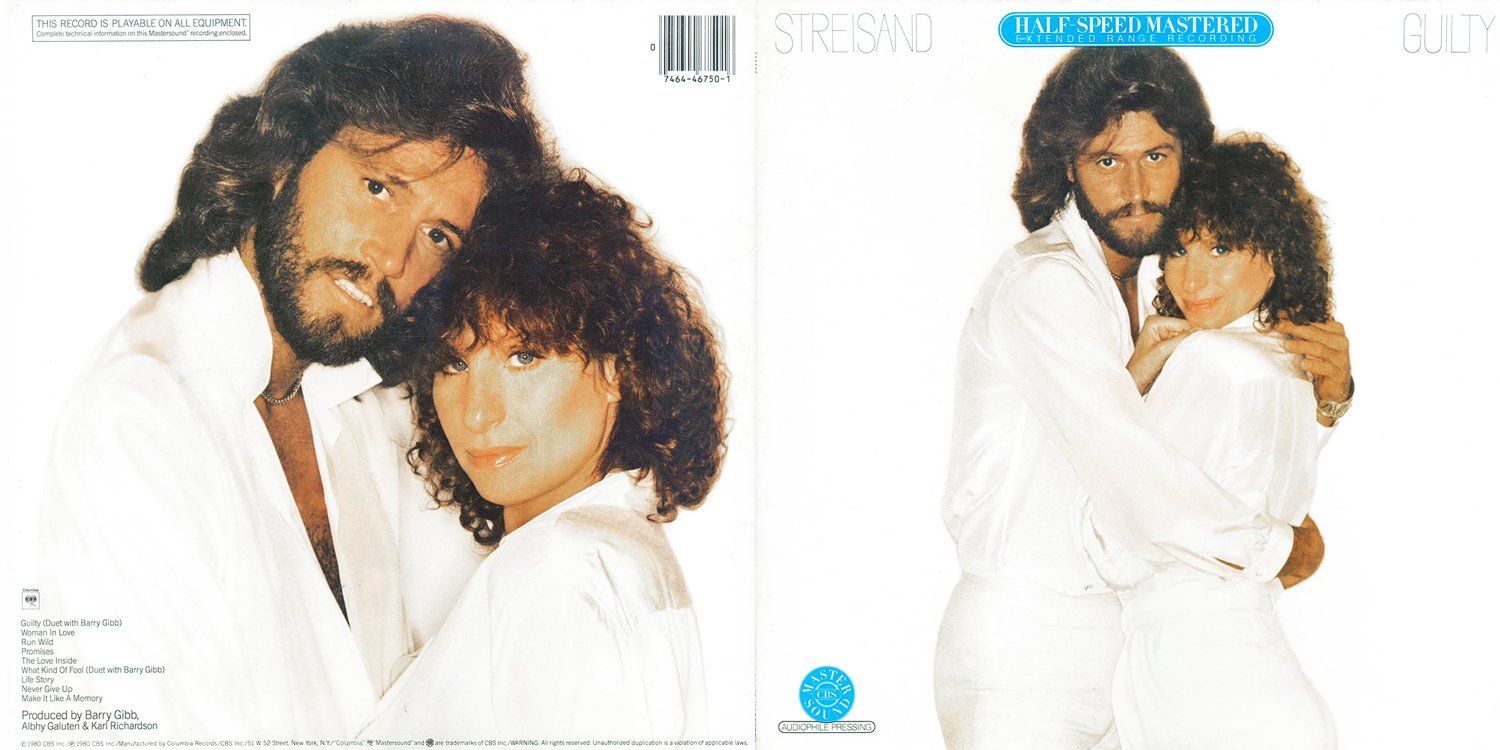

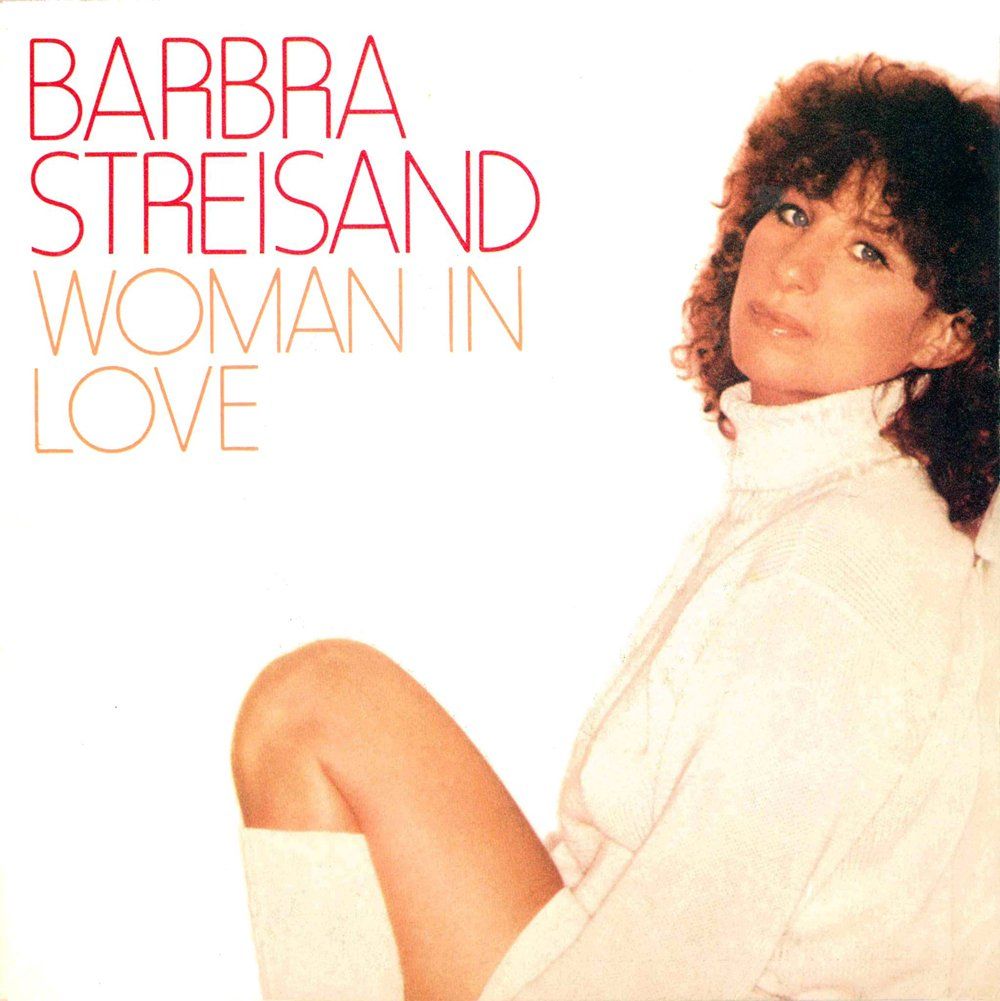

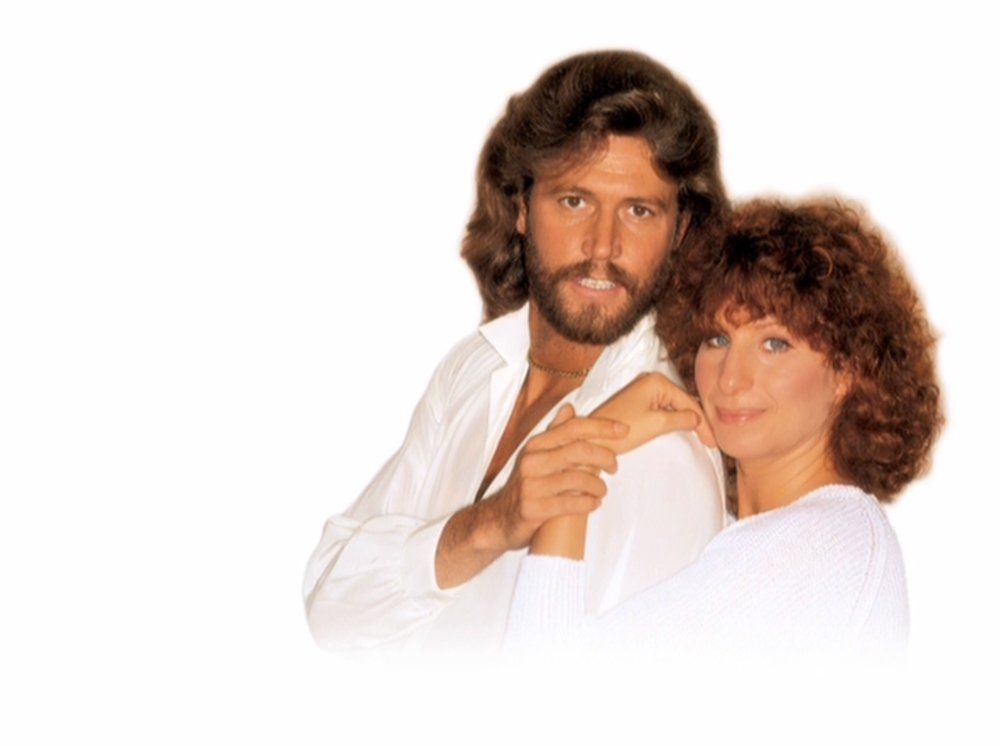

“Woman in Love”

was first single released from the album. “We and CBS both felt that it was very important for the first single not to be a duet,” Barry Gibb said. “We released the single five weeks before the album to make sure it took hold before everybody was exposed to the combined effort.”

Galuten shared his memories of recording “Make It Like A Memory,”

too. “When we were recording the song … there’s a long pause [on the chorus] when she sings ‘make it like a…memory,’ and the downbeat is supposed to be on ‘memory.’ I remember doing the demo, it took Barry, like, ten times to get the vocal to come in on time with the downbeat, because there was no time through there. There was no beat going on. For Barbra, it’s not her natural thing to sing like Michael [Jackson] or Barry rhythmically. In fact, we ended up having to do a lot of fine-tuning and adjustment to get her meter to line up in a way that was, you know, sufficiently rhythmic for Barry. But on ‘Make It Like a Memory,” she did five takes, and on every single one she nailed the downbeat. So, even though Barry has incredible detailed meter and absolute accuracy, Barbra has this intuitive sense of long-time that she knows when to come in based on some aesthetic that is not countable by the rest of us R&B musicians.”