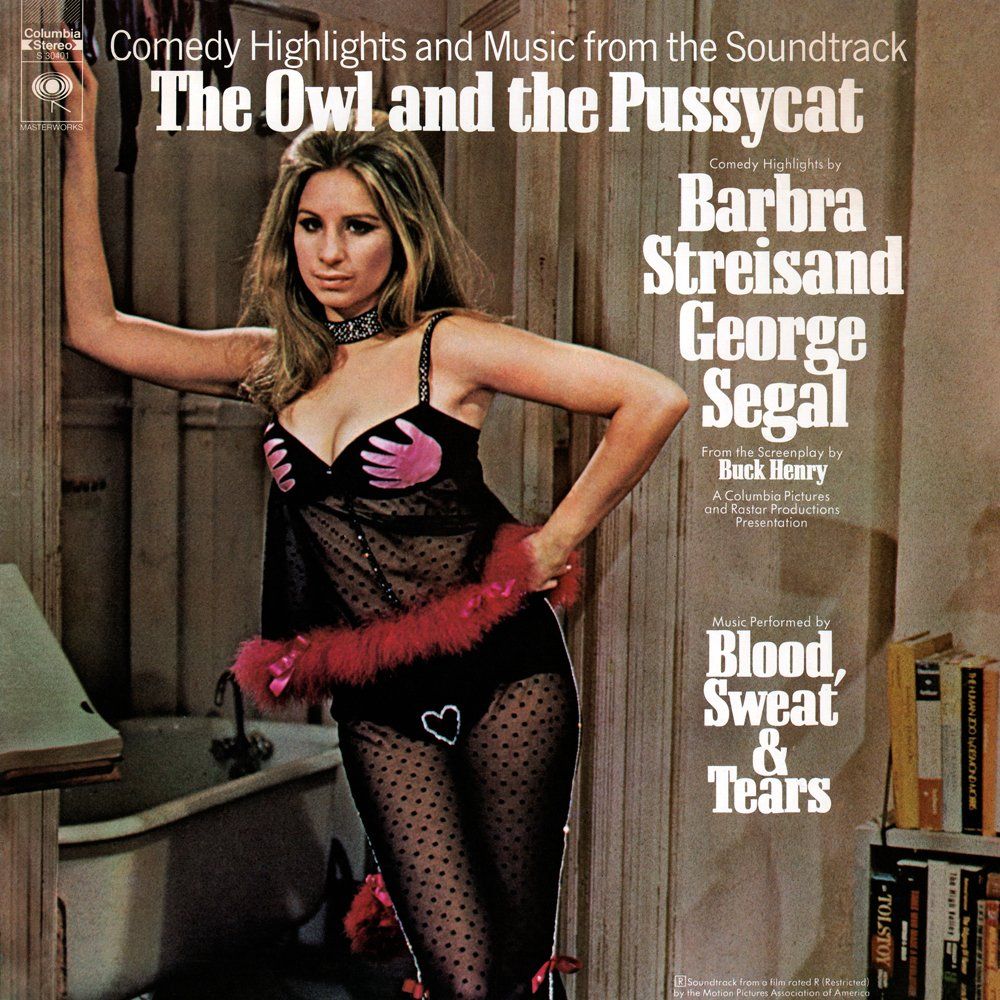

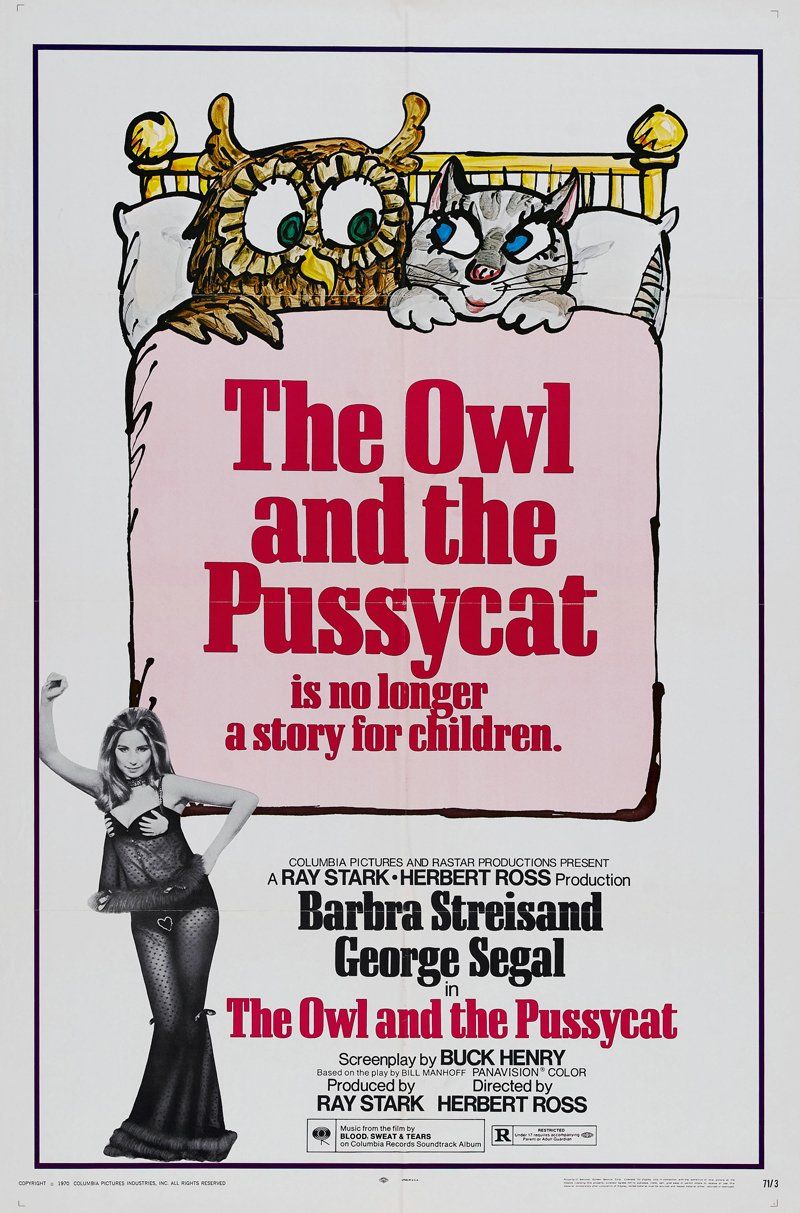

Seven Arts Productions were the high bidders for the movie rights to The Owl and the Pussycat in 1964. Stark paid $100,000 dollars, and the entertainment columns immediately reported that he offered Elizabeth Taylor the role of Doris. Taylor said she wanted Montgomery Clift as her co-star. That deal never came to fruition, so Stark revisited the property a couple of years later for Streisand, who owed him three more pictures. Her casting was announced in November 1968.

Variety reported in December 1968 that Columbia Pictures announced The Owl and the Pussycat at their stockholders meeting, with Herb Ross selected to direct. Ross handled the musical numbers in the Funny Girl movie and was finishing up his first directorial project, Goodbye Mr. Chips. Variety also speculated that Barbra’s husband, Elliott Gould, may have been considered as her male lead.

Pictured: Ray Stark and Herbert Ross

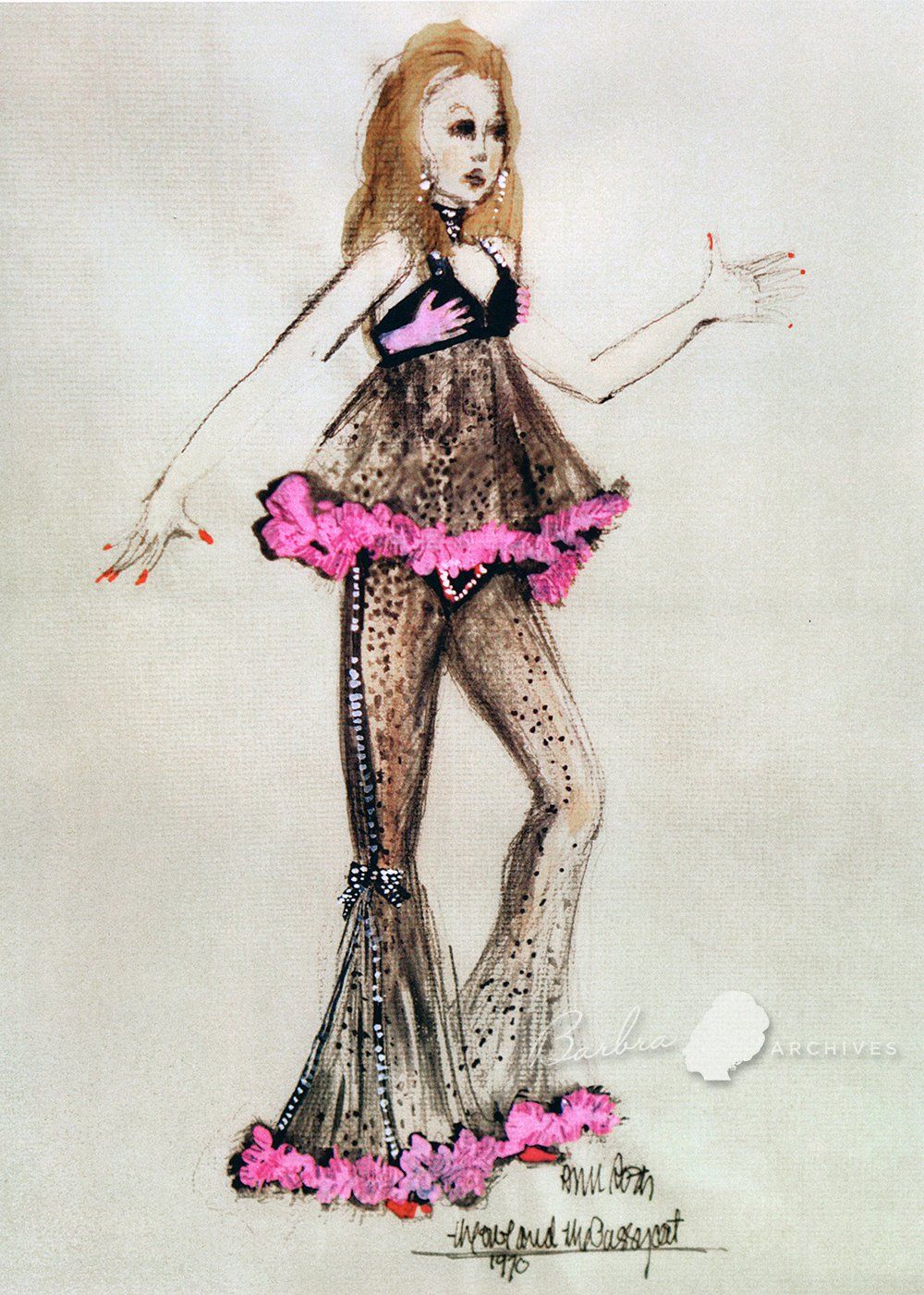

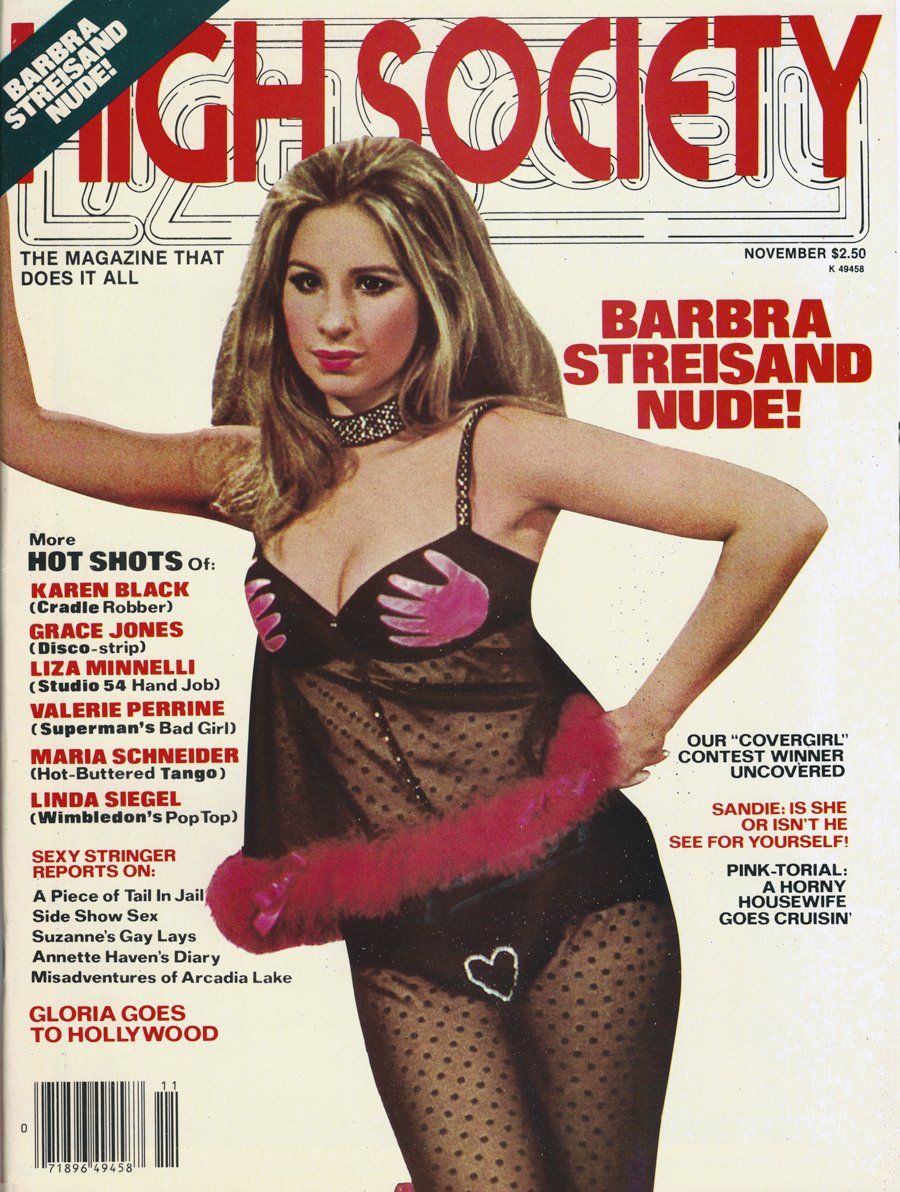

Stark and Streisand had a contentious relationship that played out in the papers when Stark told Joyce Haber that he would tailor the character of Doris for Streisand’s singing talent. “She’ll be a folkhooker,” he said. Stark imagined Doris as a part-time folksinger, incorporating some songs into the movie for Streisand to sing.

Streisand responded at a December press conference: “I will not sing in The Owl and the Pussycat despite what Ray Stark says I will do.”

Asked by another columnist if she would be singing in The Owl and the Pussycat, Streisand retorted, “How many singing prostitutes do you know?”

A week later, Stark mended fences with his star when he called up Sheilah Graham and explained that Barbra would not sing in the movie. “She wants to prove she can act without having to sing,” he said.

“Naturally, when the showdown came, I said there was no way I would sing,” Streisand told Newsday in 1972. “You see what I mean? I was pushed around. Made to feel like I was a bad little girl or something. There was no reason for that.”

Later, in 1975, Barbra explained, “People said, ‘You've got to sing in Owl and the Pussycat,’ and I said, I'm not going to sing, and they said you can't not sing. I said I'm not only going to not sing, I'm going, to not sing in at least four pictures. I'm not going to do just what I'm expected to do. It's no fun for me. I'm not afraid of failure.”

![George Segal and Barbra Streisand in public at a Halloween party, 1969. [Photo Credit: Tim Boxer]](https://lirp.cdn-website.com/c100d4ee/dms3rep/multi/opt/owl-party-1920w.jpg)