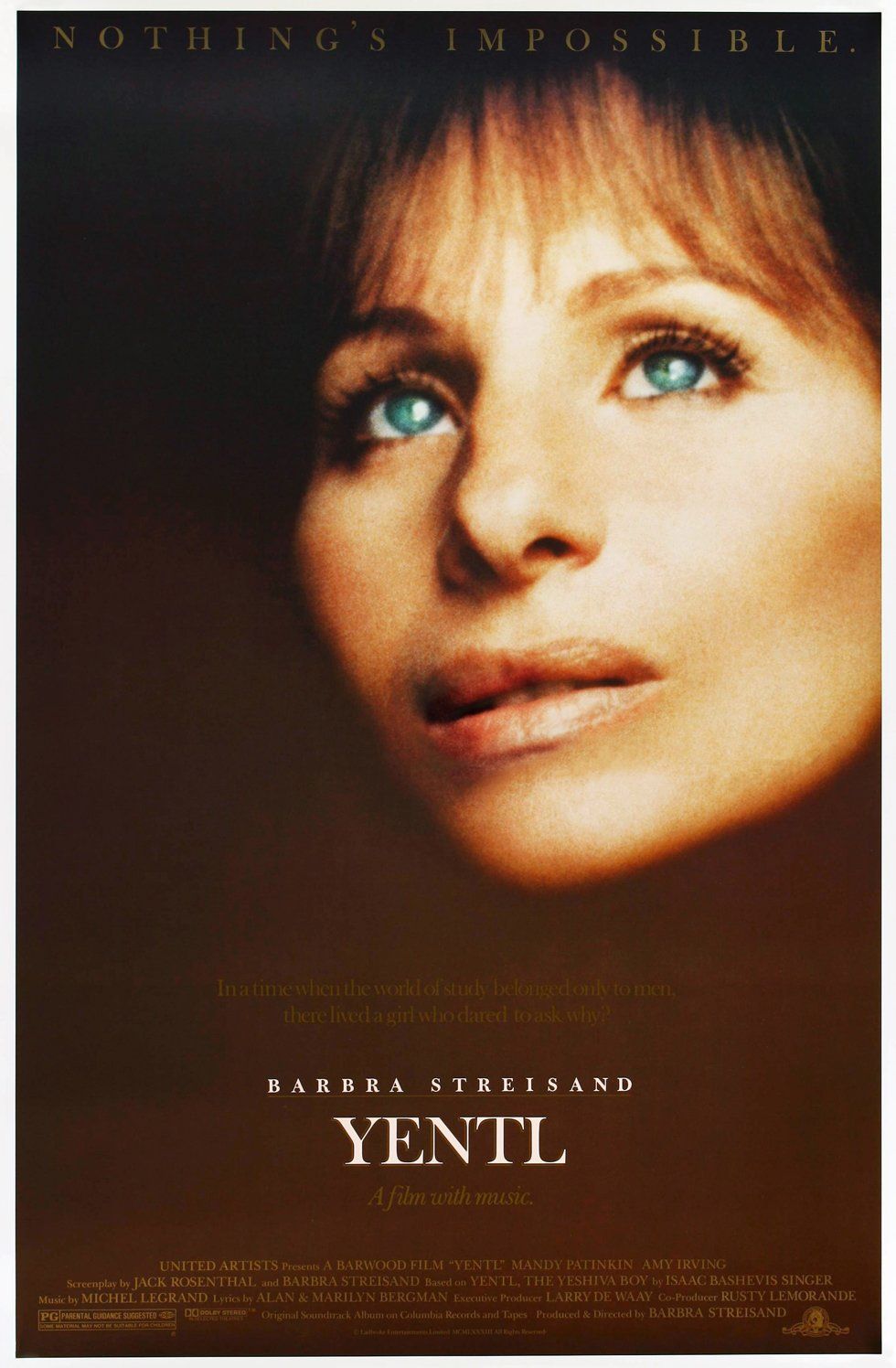

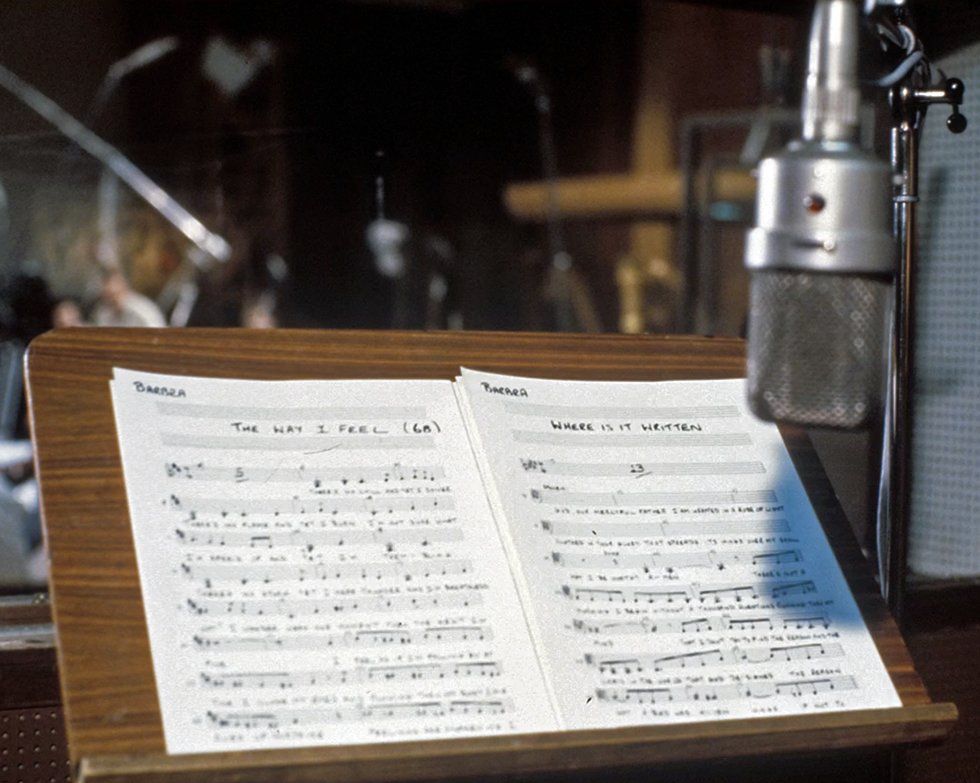

The movie Yentl is billed on its theatrical one-sheet as “a film with music.” What Streisand achieved musically, with the creative team of Michel Legrand and lyricists Marilyn and Alan Bergman, was a new sort of movie musical in which only the main character sang.

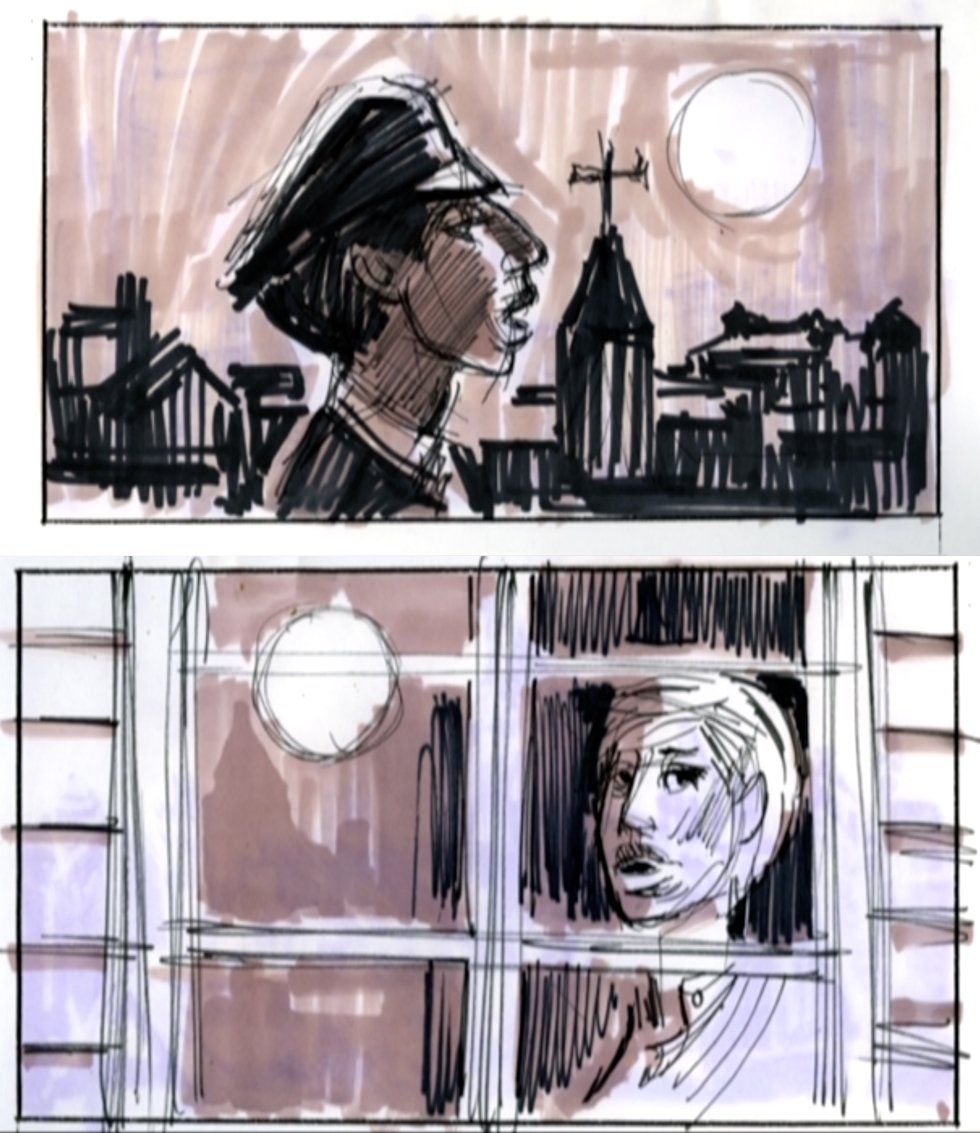

“Originally I had no intention of using music,” Streisand explained, “but I’m happy it turned out that way. Once Yentl leaves her village, she lives a secret life that cannot be shared with anyone and we all believed that the best way to capture that inner voice was in a musical narrative.”

Streisand also avoided drawing comparisons with other musical films like Fiddler on the Roof or Cabaret in which entire casts burst into song. Streisand’s concept was that only Yentl would sing her inner thoughts and feelings on screen. “We worried at first about how audiences would react to this device,” Streisand said, “but there was really no better way to reveal Yentl’s unique perspective.”

Marilyn Bergman added, “We often discussed the possibility of introducing music through the other characters. Mandy Patinkin, in fact, has a beautiful voice, but we all finally agreed not to violate the film’s musical narrative as experienced by the central character. Avigdor and Hadass are free to express themselves—it is only Yentl who can’t share her true feelings.”

Streisand admired Patinkin’s singing voice, too. “But it was out of character for the style of the movie,” she stated. “[Him singing] would make it more a conventional musical. And so I couldn’t do even though it would have been nice.”